“Text-to-image” generators – DALL·E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, or the recent module integrated into GPT-4o – are revolutionizing visual creation at a pace reminiscent of the advent of photography. The same accusations of “mechanical process” once leveled at photographers are now resurfacing against artists using AI (M. Kummer, Das urheberrechtlich schützbare Werk, Bern 1968, p. 207).

Yet, like photography in the 19th century, these tools are already embedded in creative practices where human intervention remains decisive.

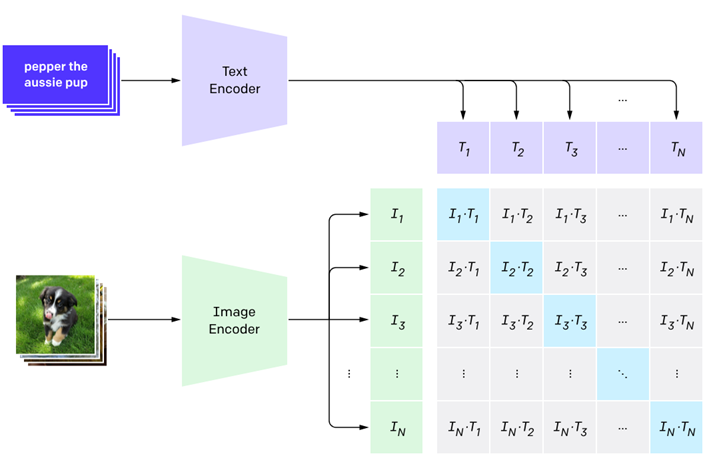

Technically, text-to-image models are first built by creating and preparing databases that link visuals to captions. These datasets are then cleaned – removing duplicates, standardizing metadata, eliminating illicit images – and linked to textual descriptions to allow classification. To perform this step, models use text and image encoders (such as OpenAI’s CLIP), which translate descriptions and pixels into shared vectors capable of capturing semantic relationships (H. Linde, So funktionieren Bild-Generatoren, 23.05.2023, https://www.golem.de/news/kuenstliche-intelligenz-so-funktionieren-ki-bildgeneratoren-2305-174436.html, accessed 25.02.2025).

Image taken from https://openai.com/index/clip/

Once the preparatory steps are completed, the AI model can be trained. Modern image generators rely on diffusion models: they gradually add noise to training images, learn how to cancel it, and then reverse the process to generate new images (Andrew, How does Stable Diffusion work?, 09.06.2024, https://stable-diffusion-art.com/how-stable-diffusion-work/, accessed 25.02.2025).

Under Swiss law, the protection of images produced by AI models must be assessed in light of the legal conditions set out in Article 2 paragraph 1 of the Copyright Act[1] (CopA): an intellectual creation, belonging to the literary or artistic domain, and possessing individual character.

The intellectual creation requires the intervention of human will. The work must thus express a manifestation of thought (Swiss Federal Court Decision, BGE 130 III 168 – Bob Marley). The legislature specifies that whenever a human will determine the outcome – for instance, in the case of computer-generated artistic works – there is indeed an intellectual creation, which is protected provided it possesses individual character (Swiss Federal Council, BBl 1989 III 465, p. 507). According to legal doctrine, the condition of intellectual creation is met as soon as the author exerts even a minimal influence on the creation (I. Cherpillod, L’objet du droit d’auteur, Lausanne 1985, p. 217).

In our view, this condition is generally fulfilled for images generated by AI models. Indeed, the link between the user and the generated image is evident: it is through the instructions given that the generation process is triggered and the image produced. Furthermore, this connection is expressed in several ways. On the one hand, the prompt’s formulation, even if brief, reflects certain intentions, tastes, and artistic preferences, already influencing the image’s aesthetics and theme. On the other hand, users typically proceed through trial and error, seeking a result aligned with their vision. Additionally, they select and retain the image that best meets their goals, possibly editing it or integrating it into a larger work.

Next, AI-generated images undeniably belong to the artistic domain, as they involve form, color, and visual composition.

As for individual character, it is assessed objectively. According to the principle of statistical uniqueness, a work is considered individual if it could not have been identically created by another author independently (I. Cherpillod, Propriété intellectuelle, Précis de droit suisse, Basel 2021, N 1065, pp. 185–186). Individuality thus contrasts with banality or routine work and distinguishes itself from the commonplace (Swiss Federal Court Decision, BGE 130 III 714, para. 2.3).

In our opinion, individual character in AI-generated images can only be recognized if the user actively intervenes in the creative process. Otherwise, the image produced by the model is merely a statistical response – banal and potentially reproducible by anyone. The degree of human involvement is therefore decisive. If the user’s conceptual work is sufficiently detailed, it can guide the AI model toward a unique result. Likewise, technical choices – such as platform selection, parameter settings, or post-production – also play a key role. It is the sum of these decisions that contributes to shaping a truly singular image.

In this respect, we can draw inspiration from case law on photography, where the protection of a work depends on the photographer’s creative decisions. Similarly, if an AI model user makes comparable choices, we believe the image’s individual character should be acknowledged.

In conclusion, we regret the excessive caution shown by many experts regarding the protection of AI-generated images. To us, this skepticism recalls the mistrust that surrounded the emergence of photography: the use of a technical tool should not exclude human creativity, but can, on the contrary, be its natural extension.

Suggested citation: Timothée Barghouth, AI-Generated Images: Human Creativity and Individual Character under Swiss Law, Blog of the LexTech Institute, 3rd June 2025

[1] Federal Act on Copyright and Related Rights (SR 231.1).